How Clinton’s ‘Basket of Deplorables’ Taught Germany a Lesson

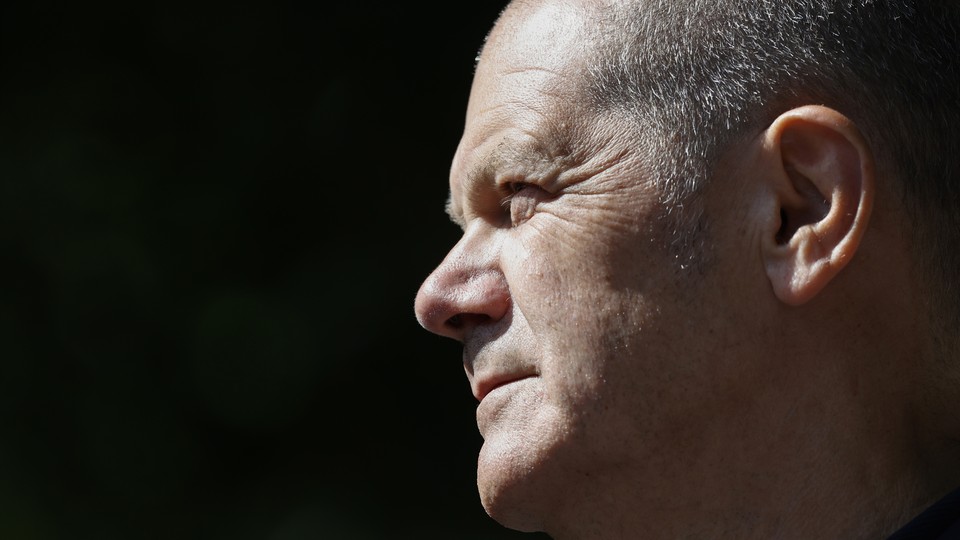

Olaf Scholz rooted his campaign in respect—and won.

In the final days of Germany’s election campaign, the center-left Social Democrats appeared to focus their final message to voters on one idea: respect. The message was plastered across the country on vibrant red posters and featured in the closing campaign speech of the party’s candidate for chancellor, Olaf Scholz, who pledged that a Germany under his leadership would recognize the contributions of everyone in society, regardless of their professional or social merit.

“We are working very hard on respect. Recognition is a question of how we live together in our societies,” Scholz told me and a small group of reporters following his final campaign rally, in the West German city of Cologne. What mattered, he said, was that Germans all felt a degree of responsibility for the future, and that none thinks “they are better than the others.”

The message, though earnest and somewhat anodyne, nevertheless contains an anti-populist pitch aimed at combatting the narrative, both in Germany and around the world, that establishment parties such as the Social Democrats are out of touch with the wants and needs of everyday “real” people. A Germany led by Scholz would, the party seemed to be arguing, respect the contributions of all Germans.

This strategy, dull though it may be, might just have worked: Preliminary official results published today showed that the Social Democrats won the largest share of votes in yesterday’s election, beating outgoing Chancellor Angela Merkel’s center-right Christian Democrats for the first time in more than a decade. Although the Social Democrats barely scraped together more than a quarter of all ballots, and the outcome of the election is still uncertain (coalition negotiations could take weeks, if not months), the results are being received as “a great success” by the party—one that other progressives can learn from.

And that is partly because Scholz and his team are open about the lessons they’ve learned from progressive parties elsewhere. Close advisers to the candidate said that while he was crafting his political message, Scholz studied two of the left’s biggest political failures in recent memory: the United States’ 2016 presidential election and Britain’s Brexit referendum. His primary takeaway from both events was that “we should, as progressives, be very careful to acknowledge all the different choices that people make about their life,” Wolfgang Schmidt, a junior finance minister and one of Scholz’s closest advisers, told me. “That’s why Olaf Scholz talked a lot about respect. Somebody without a college degree should not get the impression [that] he or she is seen as part of a ‘basket of deplorables,’” he said, referencing Hillary Clinton’s infamous gaffe about Donald Trump’s supporters.

Scholz might not disagree with Clinton’s assessment. But his point is that this kind of rhetoric isn’t the best way to reach voters. In a recent interview with The Guardian, he surmised that the main reason Britons voted for Brexit and Americans voted for Trump was that “people are experiencing deep social insecurities, and lack appreciation for what they do.” During his final campaign speech, Scholz bemoaned society’s tendency to determine people’s merit on the basis of their education or profession, noting that lawyers such as himself are no more important to society than laborers or craftspeople. By appealing to those individuals and making them feel heard, Scholz would argue, progressives can bring them back into the fold and, crucially, steer them away from the appeals of the populist right.

In some ways, Scholz’s approach speaks to the consensual nature of the German system. Although it does see some elements of name-calling and partisan attacks (Merkel’s Christian Democrats, for example, sought to cast Scholz as a harbinger of the far left, despite the fact that he currently serves as deputy chancellor in Merkel’s governing coalition), German politics hardly rivals the polarization in American and British politics. Throughout the campaign, Scholz sought to avoid any rhetoric that would make him appear overtly partisan—a move that his campaign manager, Lars Klingbeil, said was intentional.

“There are hard attacks in the election, but in the end, we know that we have to be respectful to the others because we have to work together in some coalitions,” Klingbeil, the Social Democrats’ secretary general, told me and other American journalists in a briefing, noting that one of the issues he has observed in U.S. politics is politicians’ inclination to speak to their party base rather than to the people writ large. This, he argued, not only brings about polarization, but also unnecessarily limits a candidate’s appeal. “Here,” he said, “we focus on the middle of society.”

It helps, of course, that Scholz hasn’t had to face a major populist challenger akin to Trump in the U.S. or Marine Le Pen in France. Although the far-right Alternative for Germany maintains a significant presence in German politics, support for the party has essentially flatlined since it entered Germany’s parliament, following the country’s previous federal election, in 2017. That the AfD is all but certain to be excluded from any coalition talks has allowed Germany’s mainstream parties to largely ignore it.

Scholz’s strategy has made him the front-runner to succeed Merkel as Germany’s next chancellor. Yet winning an election and retaining power are two different things, and respect has to be more than just a slogan to be effective. In the Social Democrats’ case, that means following through on the party’s pledge to address societal inequality by, among other initiatives, increasing the hourly minimum wage by 25 percent to 12 euros ($14) an hour and reintroducing a wealth tax on the country’s rich. Such promises won’t be easily fulfilled—especially if the Social Democrats are forced into coalition with the pro-business Free Democratic Party, one of the election’s kingmakers (the other being the Greens) and a fierce opponent of tax hikes.

Whether Scholz gets the chance to achieve any of these goals will be determined by coalition talks, which have already begun. Although his Social Democrats will enjoy the symbolic boost of having secured the highest number of votes, it doesn’t guarantee that Scholz will succeed Merkel.

Still, Scholz is optimistic that progressives will look to his campaign not as a failure but as a playbook.

The Friedrich Ebert Foundation (Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung) supported reporting costs for this article.