This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Artificial-intelligence experts are excited about the progress of the past few years. You can tell! They’ve been telling reporters things like “Everything’s in bloom,” “Billions of lives will be affected,” and “I know a person when I talk to it — it doesn’t matter whether they have a brain made of meat in their head.”

We don’t have to take their word for it, though. Recently, AI-powered tools have been making themselves known directly to the public, flooding our social feeds with bizarre and shocking and often very funny machine-generated content. OpenAI’s GPT-3 took simple text prompts — to write a news article about AI or to imagine a rose ceremony from The Bachelor in Middle English — and produced convincing results.

Deepfakes graduated from a looming threat to something an enterprising teenager can put together for a TikTok, and chatbots are occasionally sending their creators into crisis.

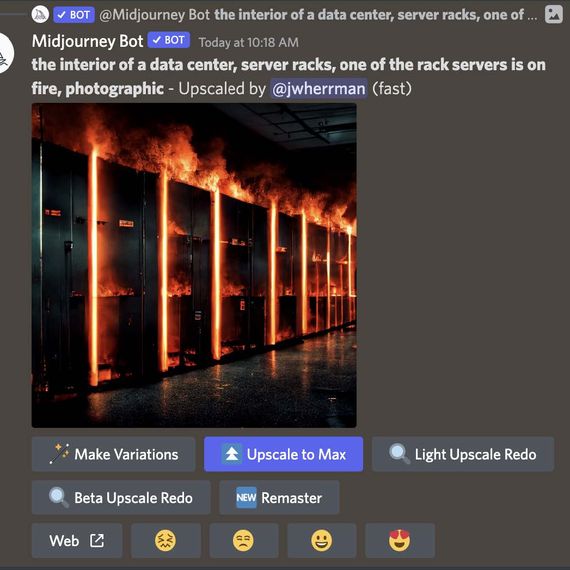

More widespread, and probably most evocative of a creative artificial intelligence, is the new crop of image-creation tools, including DALL-E, Imagen, Craiyon, and Midjourney, which all do versions of the same thing. You ask them to render something. Then, with models trained on vast sets of images gathered from around the web and elsewhere, they try — “Bart Simpson in the style of Soviet statuary”; “goldendoodle megafauna in the streets of Chelsea”; “a spaghetti dinner in hell”; “a logo for a carpet-cleaning company, blue and red, round”; “the meaning of life.”

Through a million posts and memes, these tools have become the new face of AI.

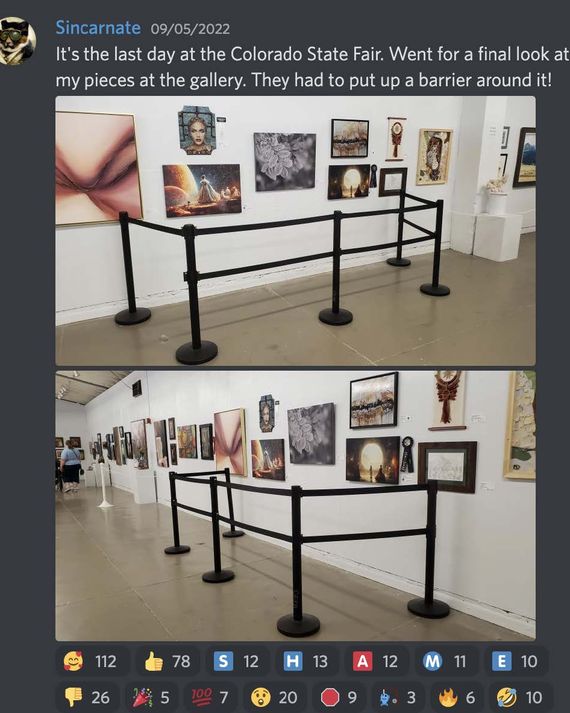

This flood of machine-generated media has already altered the discourse around AI for the better, probably, though it couldn’t have been much worse. In contrast with the glib intra-VC debate about avoiding human enslavement by a future superintelligence, discussions about image-generation technology have been driven by users and artists and focus on labor, intellectual property, AI bias, and the ethics of artistic borrowing and reproduction. Early controversies have cut to the chase: Is the guy who entered generated art into a fine-art contest in Colorado (and won!) an asshole? Artists and designers who already feel underappreciated or exploited in their industries — from concept artists in gaming and film and TV to freelance logo designers — are understandably concerned about automation. Some art communities and marketplaces have banned AI-generated images entirely.

I’ve spent time with the current versions of these tools, and they’re enormously fun. They also knock you off balance. Being able to generate images that look like photos, paintings, drawings or 3-D models doesn’t make someone an artist, or good at painting, but it does make them able to create, in material terms, some approximation of what some artists produce, instantly and on the cheap. Knowing you can manifest whatever you’re thinking about at a given moment also gestures at a strange, bespoke mode of digital communication, where even private conversations and fleeting ideas might as well be interpreted and illustrated. Why just describe things to people when you can ask a machine to show them?

Still, most discussions about AI media feel speculative. Google’s Imagen and Parti are still in testing, while apps like Craiyon are fun but degraded tech demos. OpenAI is beginning the process of turning DALL-E 2 into a mainstream service, recently inviting a million users from its wait list, while the release of a powerful open-source model, Stable Diffusion, means lots more tools are coming.

Then there’s Midjourney, a commercial product that has been open to the masses for months, through which users have been confronting, and answering, some more practical questions about AI-media generation. Specifically: What do people actually want from it, given the chance to ask?

Midjourney is unlike its peers in a few ways. It’s not part of or affiliated with a major tech company or with a broader AI project. It hasn’t raised venture capital and has just ten employees. Users can pay anywhere from $10 a month to $600 a year to generate more images, get access to new features, or acquire licensing rights, and thousands of people already have.

It’s also basically just a chat room — now, in fact, within a few months of its public launch, the largest on all of Discord, with nearly 2 million members. (For scale, this is more than twice the size of official servers for Fortnite and Minecraft.) Users summon images by prompting a bot, which attempts to fulfill their requests in a range of public rooms (#newbies, #show-and-tell, #daily-theme, etc.) or, for paid subscribers, in private direct messages. This bot passes along requests to Midjourney’s software — the “AI” — which depends on servers rented from an undisclosed major cloud provider, according to founder David Holz. Requests are effectively thrown into “a giant swirling whirlpool” of “10,000 graphics cards,” Holz said, after which users gradually watch them take shape, gaining sharpness but also changing form as Midjourney refines its work.

This hints at an externality beyond the worlds of art and design. “Almost all the money goes to paying for those machines,” Holz said. New users are given a small number of free image generations before they’re cut off and asked to pay; each request initiates a massive computational task, which means using a lot of electricity.

High compute costs — which are largely energy costs — are why other services have been cautious about adding new users. Midjourney made a choice to just pass that expense along to users. “If the goal is for this to be available broadly, the cloud needs to be a thousand times larger,” Holz said.

Setting aside, for now, the prospect of an AI-joke, image-induced energy-and-climate crisis, Midjourney’s Discord is an interesting place to lurk. Users engineer prompts in broken and then fluent Midjourney-ese, ranging from simple to incomprehensible; talk with one another about AI art; and ask for advice or critique. Before the crypto crash, I watched users crank out low-budget NFT collections, with prompts like “Iron Man in the style of Hayao Miyazaki, trading card.” Early on, especially, there were demographic tells. There were lots of half-baked joke prompts about Walter White, video-game characters rendered in incongruous artistic styles, and, despite Midjourney’s 1,000-plus banned-word list and active team of moderators, plenty of somewhat-to-very horny attempts to summon fantasy women who look like fandom-adjacent celebrities. Now, with a few hundred thousand people logged in at a time, it’s huge and disorienting.

The public parts of Midjourney Discord most resemble an industrial-scale automated DeviantArt, from which observers have suggested it has learned some common digital-art sensibilities. (DeviantArt has been flooded with Midjourney art, and some of its users are not happy.) Holz said that absent more specific instructions, Midjourney has settled on some default styles, which he describes as “imaginative, surreal, sublime, and whimsical.” (In contrast, DALL-E 2 could be said to favor photorealism.) More specifically, he said, “it likes to use teal and orange.” While Midjourney can be prompted to create images in the styles of dozens of artists living and dead, some of whom have publicly objected to the prospect, Holz said that it wasn’t deliberately trained on any of them and that some have been pleased to find themselves in the model. “If anything, we tend to have artists ask to copy them better.”

Quite often, though, you’ll encounter someone gradually painstakingly refining a specific prompt, really working on something, and because you’re in Discord, you can just ask them what they’re doing. User Pluckywood, real name Brian Pluckebaum, works in automotive-semiconductor marketing and designs board games on the side. “One of the biggest gaps from the design of a board game to releasing the board game is art,” he said. “Previously, you were stuck with working through a publisher because an individual can’t hire all these artists.” To generate the “600 to 1,000” unique pieces of art he needs for the new game he is working on — “box art, character art, rule-book art, standee art, card art, card back, board art, lore-book art” — he sends Midjourney prompts like this:

character design, Alluring and beautiful female vampire, her hands are claws and she’s licking one claw, gothic, cinematic, epic scene, volumetric lighting, extremely detailed, intricate details, painting by Jim Lee, low angle shot –testp

Midjourney sends her back in a style that is somehow both anonymous and sort of recognizable, good enough to sustain a long glance but, as is still common with most generative-image tools, with confusing hands. “I’m not approaching publishers with a white-text blank game,” Pluckebaum said. If they’re interested, they can hire artists to finish the job or clean things up; if they’re not, well, now he can self-publish.

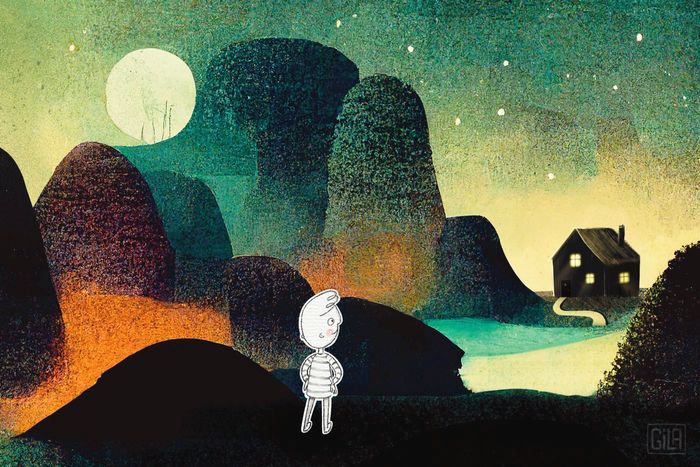

Another Midjourney user, Gila von Meissner, is a graphic designer and children’s-book author-illustrator from “the boondocks in north Germany.” Her agent is currently shopping around a book that combines generated images with her own art and characters. Like Pluckebaum, she brought up the balance of power with publishers. “Picture books pay peanuts,” she said. “Most illustrators struggle financially.” Why not make the work easier and faster? “It’s my character, my edits on the AI backgrounds, my voice, and my story.” A process that took months now takes a week, she said. “Does that make it less original?”

User MoeHong, a graphic designer and typographer for the state of California, has been using Midjourney to make what he called generic illustrations (“backgrounds, people at work, kids at school, etc.”) for government websites, pamphlets, and literature: “I get some of the benefits of using custom art — not that we have a budget for commissions! — without the paying-an-artist part.” He said he has mostly replaced stock art, but he’s not entirely comfortable with the situation. “I have a number of friends who are commercial illustrators, and I’ve been very careful not to show them what I’ve made,” he said. He’s convinced that tools like this could eventually put people in his trade out of work. “But I’m already in my 50s,” he said, “and I hope I’ll be gone by the time that happens.”

Variations of this prediction are common from different sides of the commission. An executive at an Australian advertising agency, for example, told me that his firm is “looking into AI art as a solution for broader creative options without the need for large budgets in marketing campaigns, particularly for our global clients.” Initially, the executive said, AI imagery put clients on the “back foot,” but they’ve come around. Midjourney images are becoming harder for clients to distinguish from human-generated art — and then there’s the price. “Being able to create infinite, realistic imagery time and time again has become a key selling point, especially when traditional production would have an enormous cost attached,” the executive said.

Bruno Da Silva is an artist and design director at R/GA, a marketing-and-design agency with thousands of employees around the world. He took an initial interest in Midjourney for his own side projects and quickly found uses at work: “First thing after I got an invite, I showed [Midjourney art] around R/GA, and my boss was like, ‘What the fuck is that?’”

It quickly joined his workflow. “For me, when I’m going to sell an idea, it’s important to sell the whole thing — the visual, the typeface, the colors. The client needs to look and see what’s in my head. If that means hiring a photographer or an illustrator to make something really special in a few days or a week, that’s going to be impossible,” he said. He showed me concept art that he’d shared with big corporate clients during pitches — to a mattress company, a financial firm, an arm of a tech company too big to describe without identifying — that had been inspired or created in part with Midjourney.

Image generators, Da Silva said, are especially effective at shaking loose ideas in the early stages of a project, when many designers are otherwise scrounging for references and inspiration on Google Images, Shutterstock, Getty Images, or Pinterest or from one another’s work.

These shallow shared references have led to a situation in which “everything looks the same,” Da Silva said. “In design history, people used to work really hard to make something new and unique, and we’re losing that.” This could double as a critique of art generators, which have been trained on some of the same sources and design work, but Da Silva doesn’t see it that way. “We’re already working as computers — really fast. It’s the same process, same brief, same deadline,” he said. “Now we’re using another computer to get out of that place.

“I think our industry is going to change a lot in the next three years,” he said.

I’ve been using and paying for Midjourney since June. According to Holz, I fit the most common user profile: people who are experimenting, testing limits, and making stuff for themselves, their families, or their friends. I burned through my free generations within a few hours, spamming images into group chats and work Slacks and email threads.

A vast majority of the images I’ve generated have been jokes — most for friends, others between me and the bot. It’s fun, for a while, to interrupt a chat about which mousetrap to buy by asking a supercomputer for a horrific rendering of a man stuck in a bed of glue or to respond to a shared Zillow link with a rendering of a “McMansion Pyramid of Giza.” When a friend who had been experimenting with DALL-E 2 described the tool as a place to dispose of intrusive thoughts, I nodded, scrolling back in my Midjourney window to a pretty convincing take on “Joe Biden tanning on the beach drawn by R. Crumb.”

I still use Midjourney this way, but the novelty has worn off, in no small part because the renderings have just gotten better — less “strange and beautiful” than “competent and plausible.” The bit has also gotten stale, and I’ve mapped the narrow boundaries of my artistic imagination. A lot of the AI art that has gone viral was generated from prompts that produced just the right kind of result: close enough to be startling but still somehow off, through a misinterpreted word, a strange artifact that turned the image macabre, or a fully haywire conceptual interpolation. Surprising errors are AI imagery’s best approximation of genuine creativity, or at least its most joyful. TikTok’s primitive take on an image generator, which it released last month, embraces this.

When AI art fails a little, as it has consistently in this early phase, it’s funny. When it simply succeeds, as it will more and more convincingly in the months and years ahead, it’s just, well, automation. There is a long and growing list of things people can command into existence with their phones, through contested processes kept hidden from view, at a bargain price: trivia, meals, cars, labor. The new AI companies ask, Why not art?