The 2008 financial crash ripped a giant hole in the incomes and wealth of Americans, limiting their ability to afford everything from big-ticket purchases like cars to their rent. The government declined to fill that hole in deference to a superstitious fear of deficits. This kept many millions of U.S. workers on the economy’s sidelines and myriad industrial facilities underutilized. For years, America’s capacity to produce goods and services exceeded consumers’ ability to pay for them.

This was a tragic state of affairs for the U.S. economy but, in some respects, a convenient one for American liberalism. Since the days of LBJ’s Great Society, liberals’ reform ambitions have largely focused on demand-side policy. The Affordable Care Act effectively gives Americans more money to spend on medical services through insurance subsidies. Food stamps give low-income households more money to spend on groceries. Social Security increases seniors’ disposable income.

In a demand-constrained economy, these kinds of policies are free lunches: Since there is spare productive potential, putting cash in people’s pockets not only benefits them directly but also aids the broader economy, as higher consumer spending encourages growth.

Relatedly, in an economy with relatively low inflation — like America’s from 2009 through 2020 — the government need not offset new spending with taxes in order to keep prices from shooting through the roof. And that too was very convenient for liberals, who are perennially tasked with reconciling their movement’s expansive vision for the welfare state with Americans’ aversion to higher tax rates.

But the era of weak demand is over. The COVID pandemic, and the government’s response to it, fundamentally changed our economy’s challenges. To meet them, liberals will need to change their approach to building out the welfare state and green economy. Specifically, they will need to make voters more comfortable with tax increases and themselves more comfortable with deregulation.

Joe Biden’s agenda was formulated during the decade of weak demand and bore the marks of that bygone era. The Build Back Better plan sought to drastically increase Americans’ capacity to acquire child care, health care, pre-K, higher education, housing, and elder care and establish a monthly cash benefit for nearly all households with children. Yet Biden did not ask taxpayers to pay the full bill for such expansions. Instead, the White House concealed the mismatch between its ambitions for social spending and aversion to tax hikes beneath a panoply of budget gimmicks.

By the middle of 2021, however, the economy’s free lunches had been consumed. Thanks to trillions of dollars in pandemic-relief spending, the COVID recession left no substantial hole in consumer spending, but it hammered the economy’s productive capacity. Outbreaks shuttered factories while worries about illness chased vulnerable workers out of the labor force. Meanwhile, many manufacturers expected the recession to be much deeper and longer than it was and prematurely slashed orders. When Uncle Sam started mailing out checks and cooped-up consumers began spending a massive share of their incomes on goods (instead of services), producers were caught unprepared. Demand outran supply. Inflation soared. Build Back Better gave way to the more modest Inflation Reduction Act, and Biden’s plans for greatly expanding social welfare went unfulfilled.

The age of excess supply probably isn’t coming back anytime soon. The U.S. population is old and getting older. Demand for medical services and elder care will grow even as the proportion of prime-age workers in the nation will shrink. Meanwhile, the green transition will stress the economy’s resource base: The more critical minerals needed for electric-vehicle batteries, the fewer available for cell phones; the more construction laborers needed for building transmission lines, the fewer at the housing sector’s disposal.

And if America fails to build out renewables as fast as fossil-fuel production declines, energy-price shocks could ensue. The asset manager BlackRock recently declared that America has entered a new economic regime characterized by “production constraints” and “brutal trade-offs.”

It is possible that the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate hikes will plunge the U.S. into a deep recession, thereby generating mass unemployment and tilting the supply-demand ledger. But that is not the future that liberals want. Rather, they want an America in which unemployment is virtually nonexistent, the provision of social services is vastly expanded, and the economy is rapidly decarbonized.

Liberals cannot realize that vision without sweating the details of supply-side policy. Contrary to much conservative commentary, our economy’s supply constraints have not weakened the case for Biden’s proposed expansion of social services but strengthened it. Growing America’s productive capacity requires increasing women’s labor-force participation rate, which currently trails that of men by nearly 12 percentage points. And doing that requires increasing the availability of child care.

Left to its own devices, the private sector has proved incapable of supplying an adequate number of child-care workers. As labor scarcity increased job opportunities over the past two years, 80,000 workers fled the child-care sector, typically for better-paying fields. The solution to this problem is to simultaneously increase the ability of working families to pay for child care (by giving them subsidies) and the care sector’s attractiveness to workers (by mandating higher wages). Meeting the rising demand for elder care requires similar reforms.

Yet in a supply-constrained economy, increasing demand in the care sector without triggering inflation necessitates reducing it somewhere else. That means raising taxes on ordinary Americans so that they reduce their spending on less socially vital things.

Biden famously forswore tax increases on households earning less than $400,000 a year. Liberals can no longer deficit finance their way around the problem such pledges create, which means they need a strategy for increasing the political palatability of tax hikes. In the long term, this should involve boosting voter confidence in government by improving the public sector’s performance at both supplying services and executing projects. In the short term, Democrats must lower the ceiling on the tax-exempt middle class; the party must be able to collect more revenue from households earning more than $250,000 a year.

Liberals will also need to loosen their attachment to supply-constraining regulations. America’s current regulatory framework makes it exceedingly difficult for both the public and private sectors to build housing and clean-energy infrastructure. Environmental laws that help NIMBYs kill renewable-energy projects or tie them up in court for years must be rewritten. Zoning rules that make it extremely challenging for developers to build housing in high-demand areas must be abolished.

Even in the care sector, excessive regulations stymie supply. The U.S. is currently suffering from a shortage of doctors, in no small part because of its stringent licensing requirements. Other nations also make it much easier for foreign-trained physicians to practice within their borders. But rather than fighting to reduce unnecessary licensing requirements, some liberals have recently sought to expand them by making college degrees mandatory for child-care workers.

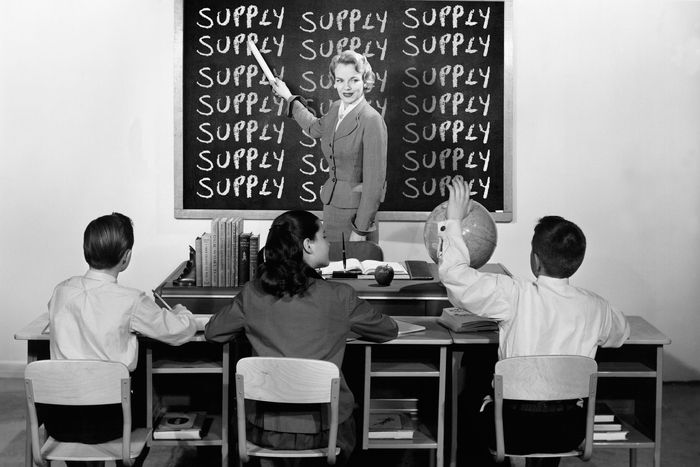

By reflexively opposing calls for deregulation, liberals do not uphold progressive ideals so much as they undermine them. An America in which housing, energy, and medical care are chronically undersupplied is one in which progressives’ vision for the country will be impossible to realize. In other words, liberals will need to develop their own supply-side economics.