Saturn’s Frozen Moon Just Got a Lot More Interesting

New evidence suggests that Enceladus has an ocean that could sustain life.

Updated at 8:16 a.m. ET on June 15, 2023.

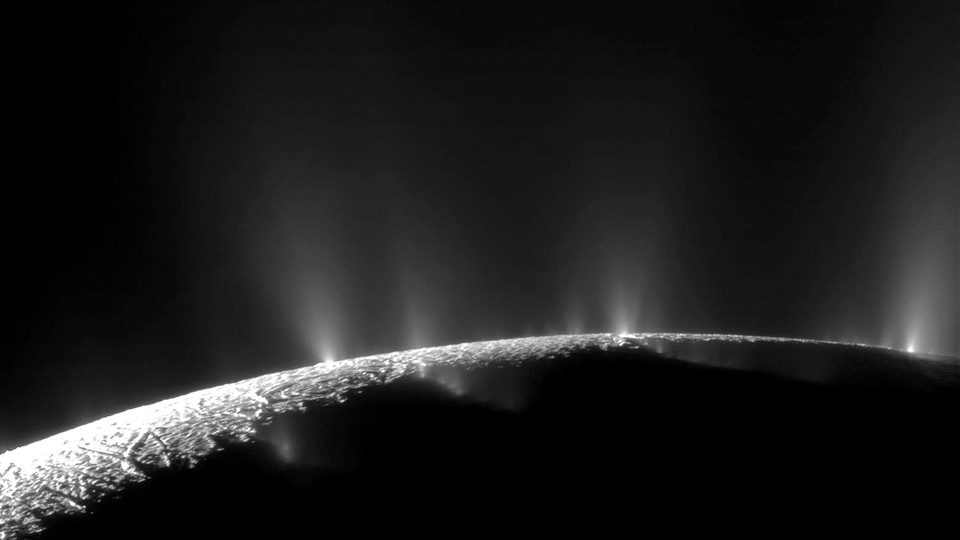

Of all the celestial bodies orbiting the sun, Enceladus shines brightest. I mean this literally: This small moon of Saturn reflects nearly all the sunlight that touches its surface, because it is covered in thick ice, radiant white and opaque. It is the picture of stillness—except at its south pole, where geysers erupt from cracks in the frozen exterior, betraying the presence of something wonderfully familiar within: a liquid ocean.

Scientists have spent years studying Enceladus and its watery plume, trying to understand the mysterious sea hidden beneath the ice. Today they have a thrilling announcement: Researchers have analyzed data collected by a spacecraft as it coasted through particles of Enceladus’s frozen spray. And in those tiny, free-floating samples of the ocean, they have discovered, for the first time, evidence of phosphorus.

What’s so interesting about phosphorus? you might ask, whispering so that the very excited scientists don’t hear you. Indeed, many of us probably haven’t thought about the element since chemistry class. But the detection of phosphorus in Enceladus’s plume—and, by extension, its subsurface ocean—is game-changing. Phosphorus is one of the six essential elements of life on Earth. It has given us the wonders of cellular membranes and DNA. The best part is that previous research had already found evidence of the other five essential elements in the vapor bursting from Enceladus. We can now say, with more confidence than ever before, that a little moon just a few planets away has a habitable ocean.

Of course, a habitable ocean does not mean an inhabited one. This discovery is not proof of alien life—far from it. But it is the first time that phosphorus has been detected in an ocean off Earth, and a sign of tremendous possibility.

Nearly everything that scientists know about Enceladus comes from a NASA spacecraft called Cassini, which spent 13 years in orbit around Saturn. Cassini zoomed through the icy particles gushing from Enceladus, some of which drift away and settle into Saturn’s orbit, forming one of the planet’s sparkly rings. In 2017, the spacecraft began to run out of fuel, so NASA tossed it into Saturn’s atmosphere, where it disintegrated—but the mission had collected loads of data that would keep scientists busy for years.

Of the fundamental components of life, phosphorus is “one of the most difficult to detect,” Bryana Henderson, a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was not involved in the research, told me. And yet, when scientists analyzed Cassini data, there it was, embedded in the minuscule grains of one of Saturn’s outermost rings, as sodium phosphate. The phosphorus likely originates in the depths of Enceladus, from chemical interactions between seawater and a mineral called apatite, which, here on Earth, is the main constituent of our teeth and bones. Such minerals “are not very soluble,” Christopher Glein, a geochemist at the Southwest Research Institute in Texas who worked on the new discovery, told me. “Your teeth don’t just dissolve when you drink a glass of water,” or when you swim at the beach. (Good!) But Enceladus’s ocean is rich in the chemical compound we know as baking soda, and the solution makes apatite easier to dissolve, releasing phosphorus into the water, Glein said.

If any life exists on Enceladus, Morgan Cable, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told me, she thinks it could resemble the creatures that thrive around Earth’s hydrothermal vents, where the sun doesn’t shine. “Here on Earth, down at the seafloor, you can see communities that have all sorts of different microbes, crabs, maybe an octopus or two, tube worms,” Cable said. Imagine a colony of Enceladus crabs under all that ice, or even Enceladus shrimp. We’re veering into speculation here about the potential life forms, but Cable said that, given the mix of elements that we now know exists on Enceladus, such life is theoretically possible.

Glein and his team say that Enceladus’s subsurface ocean might have a phosphorus concentration 100 times higher than that of the oceans on Earth—“way above what a healthy community in the Enceladus ocean would need,” Cable said. But an overabundance of phosphorus could be a sign of a rather disappointing scenario too. If any life forms were present, scientists might expect that they would consume a good chunk of that phosphorus, leaving only traces behind. Consider this example, from Cable: “If you leave a pizza out at a college campus, and no one eats it, that definitely means there’s no life around.” Cable is more hopeful than that. Perhaps, she said, “life is just getting a foothold” on Enceladus and hasn’t yet influenced the chemistry of that massive ocean.

Cable said that studying Enceladus and other frozen ocean worlds, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa and even Pluto, could bring us closer to solving that big existential question. “If you have all the ingredients for life as you know it, you mix them together, and you wait, will life form?” she said. “Or is it just super rare, and Earth is the only place in the whole universe that has life, and we’re horribly, depressingly alone? I really hope it’s not that.”

I do too. Maybe beneath that bright surface, at the bottom of the dark sea, a quiet ecosystem of microorganisms is feeding on chemical soup. These tiny aliens would be entirely unaware of our existence, and our pressing desire to prove that it’s not a lonely one. But they would be churning away, navigating their world with as much purpose as the smallest beings do on ours.

This article has been updated to clarify researchers’ confidence that Enceladus’s ocean is habitable.